-

6 mois d'abonnement pour apprendre facilement 1 langue au choix Coffret cadeau SmartboxVous avez besoin ou envie d’améliorer votre maîtrise d'une nouvelle langue ? Faites confiance à Mosalingua et bénéficiez de 6 mois d’abonnement à la nouvelle méthode MosaSeries ! Le concept est très simple : suivez une histoire addictive en langue originale. Appelée The Man With No Name, elle est divisée en plusieurs épisodes et saura vous captiver du début à la fin. Anglais, espagnol, italien, allemand ou français pour les non-francophones, à vous de choisir ! L’efficacité de l’apprentissage de ce dispositif repose sur plusieurs concepts de science cognitive et de psychologie, assurant un maximum de résultats sur votre habilité à assimiler et écouter, mais aussi sur votre capacité à enrichir votre vocabulaire et améliorer votre grammaire. Disponible sur ordinateurs, tablettes et téléphones, vous pourrez l’emmener partout avec vous !

-

15mn Par Jour Pour Apprendre L'Allemand + Cassette (Langues Vivantes)Binding : Taschenbuch, medium : Taschenbuch, ISBN : 2501028104

Germanique occidental

allemand (Deutsch [dɔʏtʃ] (![]() écoute)) est une langue germanique occidentale principalement parlée en Europe centrale. Il s'agit de la langue la plus largement parlée et officielle ou co-officielle en Allemagne, en Autriche, en Suisse, dans le Tyrol du Sud (Italie), dans la Communauté germanophone de Belgique et au Liechtenstein. C'est également l'une des trois langues officielles du Luxembourg et une langue co-officielle dans la voïvodie d'Opole en Pologne. Les langues les plus proches de l'allemand sont les autres membres de la branche germanique occidentale: afrikaans, néerlandais, anglais, frison, bas allemand / bas saxon, luxembourgeois et yiddish. Il existe également de fortes similitudes dans le vocabulaire avec le danois, le norvégien et le suédois, bien que ceux-ci appartiennent au groupe germanique nord. L'allemand est la deuxième langue germanique la plus parlée, après l'anglais.

écoute)) est une langue germanique occidentale principalement parlée en Europe centrale. Il s'agit de la langue la plus largement parlée et officielle ou co-officielle en Allemagne, en Autriche, en Suisse, dans le Tyrol du Sud (Italie), dans la Communauté germanophone de Belgique et au Liechtenstein. C'est également l'une des trois langues officielles du Luxembourg et une langue co-officielle dans la voïvodie d'Opole en Pologne. Les langues les plus proches de l'allemand sont les autres membres de la branche germanique occidentale: afrikaans, néerlandais, anglais, frison, bas allemand / bas saxon, luxembourgeois et yiddish. Il existe également de fortes similitudes dans le vocabulaire avec le danois, le norvégien et le suédois, bien que ceux-ci appartiennent au groupe germanique nord. L'allemand est la deuxième langue germanique la plus parlée, après l'anglais.

L'une des principales langues du monde, l'allemand est la première langue de près de 100 millions de personnes dans le monde et la langue maternelle la plus parlée dans l'Union européenne.[2][8] Avec le français, l'allemand est la deuxième langue étrangère de l'UE après l'anglais, ce qui en fait la deuxième langue la plus parlée de l'UE en termes de locuteur.[9] L'allemand est également la deuxième langue étrangère la plus enseignée dans l'UE après l'anglais au niveau primaire (mais la troisième après l'anglais et le français dans le premier cycle de l'enseignement secondaire),[10] la quatrième langue non anglophone la plus enseignée aux États-Unis[11] (après l'espagnol, le français et le langage des signes américain) et le deuxième langage scientifique le plus utilisé[12] ainsi que la troisième langue la plus largement utilisée sur les sites Web après l'anglais et le russe.[13] Les pays germanophones se classent au cinquième rang en termes de publication annuelle de nouveaux livres, un dixième de tous les livres (y compris les livres électroniques) du monde étant publiés en langue allemande.[14] Au Royaume-Uni, l'allemand et le français sont les langues étrangères les plus recherchées par les entreprises (49% et 50% des entreprises ayant identifié ces deux langues comme étant les plus utiles, respectivement).[15]

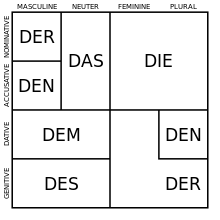

L'allemand est une langue infléchie comportant quatre cas pour les noms, les pronoms et les adjectifs (nominatif, accusatif, génitif, datif), trois genres (masculin, féminin, neutre), deux chiffres (singulier, pluriel) et des verbes forts et faibles. L'allemand tire l'essentiel de son vocabulaire de l'ancienne branche germanique de la famille des langues indo-européennes. Une partie des mots allemands sont dérivés du latin et du grec et moins empruntés au français et à l'anglais moderne. Avec des variantes standardisées légèrement différentes (allemand, autrichien et suisse standard), l'allemand est une langue pluricentrique. Il se distingue également par son large spectre de dialectes, avec de nombreuses variétés uniques en Europe et dans le monde.[2][16] En raison de l'intelligibilité limitée entre certaines variétés et l'allemand standard, ainsi que de l'absence d'une différence scientifique incontestée entre un "dialecte" et une "langue",[2] certaines variétés allemandes ou groupes de dialectes (par exemple, le bas allemand ou le plautdietsch[5]) sont également appelés "langues" ou "dialectes".[17]

Classification[[[[modifier]

L'allemand moderne standard est une langue germanique occidentale issue de la branche germanique des langues indo-européennes. Les langues germaniques sont traditionnellement subdivisées en trois branches: germanique nord, germanique oriental et germanique occidental. La première de ces branches survit en danois moderne, suédois, norvégien, féroïen et islandais, toutes issues du vieux norrois. Les langues germaniques orientales sont maintenant éteintes et le seul membre historique de cette branche d'où survivent les textes écrits est le gothique. Cependant, les langues germaniques occidentales ont subi une vaste subdivision dialectale et sont maintenant représentées dans les langues modernes telles que l'anglais, l'allemand, le néerlandais, le yiddish, l'afrikaans et d'autres.[18]

Dans le continuum des dialectes germaniques occidentaux, les lignes Benrath et Uerdingen (reliant respectivement Düsseldorf-Benrath et Krefeld-Uerdingen) permettent de distinguer les dialectes germaniques affectés par le glissement des consonnes en haut allemand (au sud de Benrath) de ceux qui le furent. pas (au nord de Uerdingen). Les différents dialectes régionaux parlés au sud de ces lignes sont regroupés en dialectes de haut allemand. (nos 29–34 sur la carte), tandis que ceux parlés au nord comprennent le bas allemand et le bas saxon (nos 19-24) et bas franconien (n ° 25) dialectes. En tant que membres de la famille des langues germaniques occidentales, le haut allemand, le bas allemand et le bas franconien peuvent encore être distingués historiquement comme irminonique, ingvaeonic et istvaeonic, respectivement. Cette classification indique leur origine historique dans les dialectes parlés par les Irminones (également connu sous le nom de groupe Elbe), Ingvaeones (ou groupe germanique de la mer du Nord) et Istvaeones (ou groupe Weser-Rhin).[18]

L'allemand standard est basé sur une combinaison de dialectes thuringien-supérieur saxon et franconien supérieur et bavarois, qui sont le dialecte allemand central et le germanophone supérieur, appartenant au groupe des dialectes irminonien haut-allemand. (nos 29–34). L’allemand est donc étroitement lié aux autres langues basées sur les dialectes du haut allemand, tels que le luxembourgeois (basé sur les dialectes de la Franconie centrale – non. 29) et le yiddish. Les dialectes du haut allemand parlés dans les pays du sud de l'allemand, tels que le suisse allemand (dialectes alemanniques), sont également étroitement liés à l'allemand standard. non. 34), et les divers dialectes germaniques parlés dans la région française du Grand Est, tels que l’alsacien (principalement alémanique, mais aussi franconien central et supérieur) (n ° 32) francophones de Lorraine (Franconian Central – non. 29).

Après ces dialectes de haut allemand, l’allemand standard est (un peu moins étroitement) apparenté aux langues basées sur les dialectes du bas franconien (par exemple, le néerlandais et l'afrikaans) ou les dialectes du bas allemand / bas saxon (parlés dans le nord de l'Allemagne et le sud du Danemark). Changement de consonne en allemand élevé. Comme on l'a noté, le premier de ces dialectes est l'istvaeonic et le dernier ingvaeonic, alors que les dialectes du haut allemand sont tous irminoniques; les différences entre ces langues et l'allemand standard sont donc considérables. L’allemand est également lié au frison: le frison septentrional (parlé en frise septentrionale) non. 28), Le frison saterlandais (parlé en saterland – non. 27), et le frison occidental (parlé en Frise – non. 26) – ainsi que les langues anglophones anglais et écossais. Ces dialectes anglo-frisons sont tous des membres de la famille ingvaeonic des langues germaniques occidentales qui ne participaient pas au changement de consonne en haut allemand.

L'histoire[[[[modifier]

Vieux haut allemand[[[[modifier]

L'histoire de la langue allemande commence avec le changement de consonne du haut allemand au cours de la période de migration, qui sépare les dialectes du vieux haut allemand (OHG) et du vieux saxon. Ce changement de son impliquait un changement radical dans la prononciation des consonnes finales vocales et non vocales (b, ré, g, et p, t, k, respectivement). Les principaux effets du changement ont été les suivants:

- Les arrêts sans voix sont devenus longs (géminés) des fricatives sans voix à la suite d'une voyelle

- Les arrêts sans voix sont devenus associés dans la position initiale du mot ou après certaines consonnes

- Les arrêts vocaux sont devenus sans voix dans certains paramètres phonétiques.[19]

| Arrêt sans voix suite à une voyelle |

Mot-initial arrêt sans voix |

Arrêt voix |

|---|---|---|

| / p / → / ff / | / p / → / pf / | / b / → / p / |

| / t / → / ss / | / t / → / ts / | / d / → / t / |

| / k / → / xx / | / k / → / kx / | / g / → / k / |

Bien qu'il existe des preuves écrites de l'ancien haut allemand dans plusieurs inscriptions sur le Futhark ancien datant du VIe siècle de notre ère (comme la boucle de Pforzen), la période du haut haut allemand commence généralement par le Abrogans (écrit entre 765 et 775), un glossaire latin-allemand fournissant plus de 3 000 mots OHG avec leurs équivalents latins. Suivant le Abrogans Les premières œuvres cohérentes écrites dans OHG apparaissent au 9ème siècle, les plus importantes étant la Les muguets, la Merseburg Charms, et le Hildebrandslied, ainsi que de nombreux autres textes religieux (le Georgslied, la Ludwigslied, la Evangelienbuchet traduit des cantiques et des prières).[19][20] le Les muguets est un poème chrétien écrit en dialecte bavarois offrant un récit de l’âme après le jugement dernier, et le Merseburg Charms sont des transcriptions de sorts et de charmes de la tradition païenne germanique. L’intérêt particulier des chercheurs a toutefois été la Hildebrandslied, un poème épique laïque racontant l'histoire d'un père et d'un fils séparés qui se sont rencontrés sans le savoir, au combat. Sur le plan linguistique, ce texte est très intéressant en raison de l'utilisation mixte de dialectes vieux saxon et vieux haut-allemand dans sa composition. Les œuvres écrites de cette période proviennent principalement des groupes Alamanni, Bavarois et Thuringien, tous appartenant au groupe germanique de l’Elbe (Irminones), établi dans l’actuelle Allemagne, l’Autriche et le Centre-Sud, entre le IIe et le VIe siècle. grande migration.[19]

En général, les textes restants de OHG montrent un large éventail de diversité dialectale avec très peu d'uniformité écrite. La première tradition écrite de OHG a survécu principalement grâce aux monastères et aux scriptoria, traduits localement en originaux latins; en conséquence, les textes survivants sont écrits dans des dialectes régionaux très disparates et exercent une influence latine non négligeable, notamment sur le vocabulaire.[19] À ce stade, les monastères, où sont produites la plupart des œuvres écrites, étaient dominés par le latin, et l’allemand n’était utilisé que de temps en temps dans l’écriture officielle et ecclésiastique.

La langue allemande de l’époque OHG était encore principalement une langue parlée, avec une vaste gamme de dialectes et une tradition orale beaucoup plus étendue que la tradition écrite. Venant tout juste de sortir du changement de consonne en haut allemand, OHG est également une langue relativement nouvelle et instable, qui subit encore de nombreux changements phonétiques, phonologiques, morphologiques et syntaxiques. La rareté du travail écrit, l'instabilité de la langue et l'analphabétisme généralisé de l'époque expliquent donc le manque de standardisation jusqu'à la fin de la période OHG en 1050.

Moyen haut allemand[[[[modifier]

Vieux frison (Alt-Friesisch)

Vieux saxon (Alt-Sächsisch)

Ancien franconien (Alt-Fränkisch)

Ancien alémanique (Alt-Alemannisch)

Vieux bavarois (Alt-Bairisch)

Bien qu’il n’y ait pas d’accord complet sur les dates de la période du haut haut allemand (MHG), on pense généralement qu’il dure de 1050 à 1350.[21][22] Ce fut une période d'expansion significative du territoire géographique occupé par les tribus germaniques et, par conséquent, du nombre de germanophones. Alors que, pendant la période du haut haut allemand, les tribus germaniques ne s’étendaient que jusqu’à l’est, comme l’Elbe et la Saale, la période MHG a vu un certain nombre de ces tribus s’étendre au-delà de cette frontière orientale pour s’étendre au territoire slave. Ostsiedlung). Parallèlement à la richesse croissante et à l'étendue géographique des groupes germaniques, on a eu de plus en plus recours à l'allemand devant les tribunaux des nobles en tant que langue standard des procédures et de la littérature officielles.[22][23] Un exemple clair de ceci est le mittelhochdeutsche Dichtersprache employé par le tribunal de Hohenstaufen en Souabe en tant que langue écrite standardisée dialectale. Alors que ces efforts étaient encore liés régionalement, l'allemand a commencé à être utilisé à la place du latin pour certaines finalités officielles, d'où un besoin accru de régularité dans les conventions écrites.

Bien que les changements majeurs de la période MHG aient été socioculturels, l’allemand subissait encore des changements linguistiques importants en syntaxe, en phonétique et en morphologie (par exemple, la diphtongaison de certaines voyelles): hus (OHG "maison")→ haus (MHG) et affaiblissement des voyelles courtes non stressées en schwa [ə]: taga ("Jours" OHG) →tage (MHG)).[24]

Une grande richesse de textes survit de la période MHG. De manière significative, ce répertoire comprend un certain nombre d’œuvres profanes impressionnantes, telles que Nibelungenlied, un poème épique racontant l’histoire de Siegfried, un tueur de dragons (v. XIIIe siècle), et Iwein, Hartmann von Aue (vers 1203), un poème arthurien, ainsi que plusieurs poèmes lyriques et romans de cour, tels que Parzival et Tristan. (À noter également le Sachsenspiegel, le premier livre de lois écrit au milieu Faible Allemand (c. 1220)). L'abondance et surtout le caractère laïc de la littérature de la période MHG témoignent des débuts d'une forme écrite standardisée de l'allemand, ainsi que du désir des poètes et des auteurs d'être compris par des individus en termes supral dialectaux.

On considère généralement que la période du Moyen Haut allemand se termine avec la décimation de la population européenne dans la peste noire de 1346–1353.[21]

Début du nouveau haut allemand[[[[modifier]

L'allemand moderne commence avec la période du début du nouveau haut allemand (ENHG), que date de 1350–1650 le philologue allemand influent Wilhelm Scherer, qui s'achève avec la fin de la guerre de trente ans.[21] Cette période a été marquée par le déplacement du latin par l’allemand en tant que langue principale des procédures judiciaires et, de plus en plus, de la littérature dans les États allemands. Tandis que ces États étaient toujours sous le contrôle du Saint Empire romain germanique et loin de toute forme d'unification, le désir d'une langue écrite cohérente et compréhensible à travers les nombreuses principautés et royaumes germanophones était plus fort que jamais. En tant que langue parlée, l'allemand est resté fortement fracturé au cours de cette période avec un grand nombre de dialectes régionaux souvent incompréhensibles et parlés dans tous les états allemands; l'invention de l'imprimerie vers 1440 et la publication de la traduction vernaculaire de la Bible par Luther en 1534 eurent cependant un effet immense sur la normalisation de l'allemand en tant que langue écrite suprac dialectale.

La période ENHG a vu la montée de plusieurs formes de chancellerie allemandes interrégionales importantes, dont une gemeine tiutsch, utilisé à la cour de l'empereur romain germanique Maximilian I, et l'autre être Meißner Deutsch, utilisé dans l’électorat de Saxe dans le Duché de Saxe-Wittenberg.[25] Parallèlement à ces normes écrites courtoises, l’invention de la presse à imprimer a conduit au développement de plusieurs langues d’imprimeurs (Druckersprachen) visant à rendre le matériel imprimé lisible et compréhensible dans le plus grand nombre possible de dialectes allemands.[26] La plus grande facilité de production et la disponibilité accrue de textes écrits ont entraîné une normalisation accrue de la forme écrite de la langue allemande.

L'un des événements centraux du développement d'ENHG a été la publication par Luther de la traduction de la Bible en allemand (le Nouveau Testament en 1522 et l'Ancien Testament, publiés en partie et achevés en 1534). Luther a basé sa traduction principalement sur le Meißner Deutsch de Saxe,[27] passant beaucoup de temps parmi la population de Saxe à la recherche du dialecte afin de rendre l'œuvre aussi naturelle et accessible que possible aux locuteurs germanophones. Des copies de la Bible de Luther comportaient une longue liste de glossines pour chaque région traduisant des mots inconnus de la région dans le dialecte régional. Au sujet de sa méthode de traduction, Luther dit ce qui suit:

Celui qui parle allemand ne demande pas au latin comment il le fera; il doit demander à la mère à la maison, aux enfants de la rue, à l'homme du marché et noter soigneusement comment ils parlent, puis traduire en conséquence. Ils comprendront alors ce qu'on leur dit car c'est allemand. Quand le Christ dit «ex abondantia cordis os loquitur», je traduirais, si je suivais les papistes, aus dem Überflusz des Herzens redet der Mund. Mais dis-moi, est-ce que ça parle allemand? Quel allemand comprend de telles choses? Non, la mère à la maison et l'homme ordinaire dirait: Wesz das Herz voll ist, des gehet der Mund über.[28]

Avec la traduction de la Bible par Luther en langue vernaculaire, l'allemand s'est affirmé contre la prédominance du latin en tant que langue légitime pour la matière courtoise, littéraire et désormais ecclésiastique. De plus, sa Bible était omniprésente dans les États allemands et presque chaque ménage en possédait un exemplaire.[29] Néanmoins, même avec l'influence de la Bible de Luther en tant que norme écrite non officielle, ce n'est qu'au milieu du 18ème siècle après la période ENHG qu'une norme largement acceptée pour l'allemand écrit est apparue.[30]

Empire autrichien[[[[modifier]

L'allemand était la langue du commerce et du gouvernement dans l'empire des Habsbourg, qui englobait une grande partie de l'Europe centrale et orientale. Jusqu'au milieu du XIXe siècle, il était essentiellement la langue des citadins dans la majeure partie de l'Empire. Son utilisation indiquait que le locuteur était un commerçant ou une personne d’une région urbaine, quelle que soit sa nationalité.

Certaines villes, telles que Prague (allemand: Prag) et Budapest (Buda, allemand: Ofen), ont été progressivement germanisées dans les années qui ont suivi leur incorporation au domaine des Habsbourg. D'autres, comme Pozsony (allemand: Pressburg, maintenant Bratislava), ont été installés à l’époque des Habsbourg et étaient principalement allemands à cette époque. Prague, Budapest et Bratislava ainsi que des villes comme Zagreb (allemand: Agram) et Ljubljana (allemand: Laibach), comprenait d'importantes minorités allemandes.

Dans les provinces orientales du Banat et de la Transylvanie (allemand: Siebenbürgen), L’allemand était la langue prédominante non seulement dans les grandes villes – comme le Temeswar (Timișoara), Hermannstadt (Sibiu) et Kronstadt (Brașov) – mais aussi dans de nombreuses petites localités des environs.[31][32]

Standardisation[[[[modifier]

Le guide le plus complet sur le vocabulaire de la langue allemande se trouve au sein de la Deutsches Wörterbuch. Ce dictionnaire a été créé par les frères Grimm et se compose de 16 parties qui ont été publiées entre 1852 et 1860.[33] En 1872, les règles grammaticales et orthographiques sont apparues pour la première fois dans Manuel Duden.[34]

En 1901, la 2ème conférence orthographique se termina par une standardisation complète de la langue allemande dans sa forme écrite et la Manuel Duden a été déclaré sa définition standard.[35] le Deutsche Bühnensprache (littéralement, langue de scène allemande) avait établi des conventions pour la prononciation allemande en théâtre (Bühnendeutsch[36]) trois ans plus tôt; toutefois, il s’agissait d’une norme artificielle qui ne correspondait à aucun dialecte parlé traditionnel. Elle reposait plutôt sur la prononciation de l’allemand standard dans le nord de l’Allemagne, bien qu’elle ait par la suite souvent été considérée comme une norme normative générale, malgré des traditions de prononciation différentes, en particulier dans les régions de langue allemande supérieure, qui caractérisent encore aujourd'hui le dialecte de la région – en particulier la prononciation de la fin -ig comme [ɪk] au lieu de [ɪç]. Dans le nord de l'Allemagne, l'allemand standard était une langue étrangère pour la plupart des habitants, dont les dialectes natifs étaient des sous-ensembles du bas allemand. On ne le rencontrait généralement que par écrit ou par un discours formel; en fait, la majeure partie de l'allemand standard était une langue écrite, qui ne correspond à aucun dialecte parlé, dans toute la région germanophone jusqu'au 19ème siècle.

Les révisions officielles de certaines règles de 1901 ne furent publiées que lorsque la réforme controversée de l'orthographe allemande de 1996 fut adoptée comme norme officielle par les gouvernements de tous les pays de langue allemande.[37] Les œuvres médiatiques et écrites sont maintenant presque toutes produites en allemand standard (souvent appelé Hochdeutsch, "Haut allemand") qui est compris dans toutes les régions où l’allemand est parlé.

Distribution géographique[[[[modifier]

Répartition approximative des locuteurs de langue maternelle allemande (en supposant un total arrondi de 95 millions) dans le monde.

Allemagne (78,3%)

Autriche (8,4%)

Suisse (5,6%)

Italie (Tyrol du Sud) (0,4%)

Autre (7.3%)

La diaspora allemande et l’allemand étant la deuxième langue la plus parlée en Europe et la troisième langue étrangère la plus enseignée aux États-Unis.[11] et l'UE (dans l'enseignement secondaire supérieur)[38] entre autres, la répartition géographique des germanophones (ou "germanophones") s'étend à tous les continents habités. En ce qui concerne le nombre de locuteurs de toutes les langues dans le monde, une évaluation est toujours compromise par le manque de données suffisantes et fiables. Pour un nombre exact et global de germanophones, l’existence de plusieurs variétés dont le statut de "langues" ou de "dialectes" distincts est contesté pour des raisons politiques et / ou linguistiques, y compris des variétés quantitativement fortes comme certaines formes de Alémanique (par exemple, alsacien)[2] et bas allemand / Plautdietsch.[5] La plupart du temps, en fonction de l'inclusion ou de l'exclusion de certaines variétés, on estime qu'entre 90 et 95 millions de personnes parlent l'allemand comme première langue.[2][17][39] 10 à 25 millions en tant que langue seconde,[2][17] et 75 à 100 millions en tant que langue étrangère.[2][3] Cela impliquerait environ 175 à 220 millions de germanophones dans le monde.[40] On estime que toutes les personnes qui suivent ou ont suivi des cours d’allemand, c’est-à-dire quel que soit leur niveau de compétence actuel, représenteraient environ 280 millions de personnes dans le monde ayant au moins quelques connaissances de l’allemand.[2]

Europe et Asie[[[[modifier]

L'allemand est une langue co-officielle, mais pas la première langue de la majorité de la population

L'allemand (ou un dialecte allemand) est une langue minoritaire reconnue par la loi (carrés: répartition géographique trop dispersée / petite à l'échelle de la carte)

L'allemand (ou une variété d'allemand) est parlé par une minorité non négligeable, mais n'a aucune reconnaissance légale

Sprachraum allemand[[[[modifier]

En Europe, l’allemand est la deuxième langue maternelle la plus parlée (après le russe) et la deuxième langue en termes de nombre de locuteurs (après l’anglais). La région de l'Europe centrale où la majorité de la population parle l'allemand en tant que première langue et dont l'allemand est une (co) langue officielle s'appelle le "Sprachraum allemand". Il comprend environ 88 millions de locuteurs natifs et 10 millions de personnes qui parlent l’allemand comme seconde langue (immigrés, par exemple).[2][17] À l’exclusion des langues minoritaires régionales, l’allemand est la seule langue officielle du pays.

C'est une langue co-officielle de la

En dehors du Sprachraum[[[[modifier]

Bien que les expulsions et l'assimilation (forcée) qui ont suivi les deux guerres mondiales les aient grandement diminuées, des communautés minoritaires composées essentiellement de locuteurs allemands, principalement bilingues, existent dans les zones adjacentes au Sprachraum et séparées de ce dernier.[2]

En Europe et en Asie, l’allemand est une langue minoritaire reconnue dans les pays suivants:

En France, les variétés alsaciennes et francophones de Franconie germanophones sont identifiées comme des "langues régionales", mais la Charte européenne des langues régionales ou minoritaires de 1998 n'a pas encore été ratifiée par le gouvernement.[47] Aux Pays-Bas, le limbourgeois, le frison et le bas allemand sont des langues régionales protégées au sens de la Charte européenne des langues régionales ou minoritaires;[41] cependant, ils sont largement considérés comme des langues séparées et ne sont ni les dialectes allemand ni néerlandais.

Afrique[[[[modifier]

Namibie[[[[modifier]

La Namibie était une colonie de l'empire allemand de 1884 à 1919. Descendant principalement des colons allemands qui ont immigré à cette époque, 25 à 30 000 personnes parlent encore l'allemand comme langue maternelle aujourd'hui.[48] La période du colonialisme allemand en Namibie a également conduit à l'évolution d'une langue pidgin standard basée sur l'allemand appelée "allemand noir namibien", qui est devenue la deuxième langue de certaines parties de la population autochtone. Bien qu'il soit presque éteint aujourd'hui, certains Namibiens plus âgés en ont encore quelques connaissances.[49]

L'allemand, avec l'anglais et l'afrikaans, était une langue co-officielle de la Namibie de 1984 à son indépendance de l'Afrique du Sud en 1990. À ce stade, le gouvernement namibien perçoit l'afrikaans et l'allemand comme des symboles de l'apartheid et du colonialisme, et a décidé que l'anglais serait le seule langue officielle, affirmant qu’il s’agissait d’une langue "neutre", car il n’existait pratiquement pas d’anglophones en Namibie à cette époque.[48] L'allemand, l'afrikaans et plusieurs langues autochtones sont devenus des "langues nationales" en vertu de la loi, les identifiant comme des éléments du patrimoine culturel de la nation et garantissant que l'État reconnaît et soutient leur présence dans le pays.[2] Aujourd’hui, l’allemand est utilisé dans une grande variété de domaines, notamment les affaires et le tourisme, ainsi que dans les églises (notamment l’Église évangélique luthérienne germanophone de Namibie (GELK)), les écoles (par exemple, Deutsche Höhere Privatschule Windhoek), de la littérature (les auteurs germano-namibiens incluent Giselher W. Hoffmann), de la radio (la Namibian Broadcasting Corporation produit des programmes radiophoniques en allemand) et de la musique (par exemple, l’artiste EES). le Allgemeine Zeitung est l'un des trois plus grands journaux de Namibie et le seul quotidien de langue allemande en Afrique.[48]

Afrique du Sud[[[[modifier]

Principalement originaires de différentes vagues d'immigration aux 19e et 20e siècles, environ 12 000 personnes parlent l'allemand ou une variété allemande comme première langue en Afrique du Sud.[50] Une des plus grandes communautés est composée des orateurs de "Nataler Deutsch",[51] une variété de bas allemand, concentrée dans et autour de Wartburg. La petite ville de Kroondal, dans la province du Nord-Ouest, compte également une population essentiellement germanophone. La constitution sud-africaine identifie l'allemand en tant que langue "couramment utilisée" et le conseil pan-sud-africain des langues est tenu de le promouvoir et de le respecter.[52] La communauté est suffisamment forte pour que plusieurs écoles internationales allemandes soient soutenues, telles que la Deutsche Schule Pretoria.

Amérique du Nord[[[[modifier]

Aux États-Unis, les États du Dakota du Nord et du Sud sont les seuls États où l'allemand est la langue la plus parlée à la maison après l'anglais.[53] Les noms géographiques allemands peuvent être trouvés dans toute la région du Midwest du pays, comme New Ulm et de nombreuses autres villes du Minnesota; Bismarck (capitale de l'État du Dakota du Nord), Munich, Karlsruhe et Strasbourg (nommée d'après une ville proche d'Odessa en Ukraine)[54] dans le Dakota du Nord; New Braunfels, Fredericksburg, Weimar et Muenster au Texas; Corn (anciennement Korn), Kiefer et Berlin dans l’Oklahoma; et Kiel, Berlin et Germantown dans le Wisconsin.

Amérique du sud[[[[modifier]

Brésil[[[[modifier]

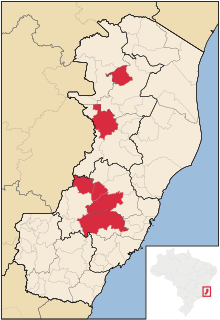

Au Brésil, les plus grandes concentrations de germanophones se trouvent dans les États de Rio Grande do Sul (où Riograndenser Hunsrückisch s'est développé), Santa Catarina, Paraná, São Paulo et Espírito Santo.[55]

Statuts co-officiels de variétés allemandes ou allemandes au Brésil[[[[modifier]

Autres pays d'Amérique du Sud[[[[modifier]

Il existe également des concentrations importantes de descendants de langue allemande en Argentine, au Chili, au Paraguay, au Venezuela, au Pérou et en Bolivie.[50]

L’impact de l’immigration allemande au XIXe siècle dans le sud du Chili a été tel que Valdivia a été pendant un temps une ville bilingue hispano-allemande "Des panneaux et des pancartes allemands aux côtés des espagnols".[62] Le prestige[note 4] la langue allemande lui a fait acquérir les qualités d'un superstrat au sud du Chili.[64] Le mot pour la mûre, une usine d'ubiquituos dans le sud du Chili, est murra au lieu du mot espagnol ordinaire mora et zarzamora de Valdivia à l'archipel de Chiloé et certaines villes de la région d'Aysén.[64] L'utilisation de rr est une adaptation de sons gutturaux trouvés en allemand difficiles à prononcer en espagnol.[64] De même, le nom des billes, un jeu traditionnel pour enfants, est différent dans le sud du Chili par rapport aux régions plus au nord. De Valdivia à Aysén, ce jeu s’appelle bochas contrairement à la parole bolitas utilisé plus au nord.[64] Le mot bocha est probablement dérivé des Allemands bocciaspiel.[64]

Océanie[[[[modifier]

En Australie, l'État de l'Australie-Méridionale a connu une vague d'immigration prononcée dans les années 1840 en provenance de Prusse (en particulier de la région de Silésie). Avec l'isolement prolongé des autres locuteurs allemands et le contact avec l'anglais australien, un dialecte unique appelé le barossa allemand s'est développé et est parlé principalement dans la vallée de Barossa, près d'Adélaïde. L'utilisation de l'allemand a fortement diminué avec l'avènement de la Première Guerre mondiale, en raison du sentiment anti-allemand dominant au sein de la population et de l'action gouvernementale correspondante. Il a continué à être utilisé comme langue maternelle au XXe siècle, mais son utilisation est maintenant limitée à quelques locuteurs plus âgés.[[[[citation requise]

Au 19ème siècle, l'immigration allemande en Nouvelle-Zélande était moins marquée que celle en provenance de Grande-Bretagne, d'Irlande et peut-être même de Scandinavie. Malgré cela, il existait d'importantes poches de communautés germanophones qui ont duré jusqu'aux premières décennies du XXe siècle. Les germanophones se sont établis principalement à Puhoi, Nelson et Gore. Lors du dernier recensement (2013), 36 642 personnes en Nouvelle-Zélande parlaient allemand, ce qui en fait la troisième langue européenne la plus parlée après l'anglais et le français et, globalement, la neuvième langue la plus parlée.[65]

Il existe également un important créole allemand à l’étude et à la récupération, nommé Unserdeutsch, parlée dans l’ancienne colonie allemande de Nouvelle-Guinée allemande, dans toute la Micronésie et dans le nord de l’Australie (c’est-à-dire les régions côtières du Queensland et de l’Australie occidentale), par quelques personnes âgées. Le risque de son extinction est sérieux et les chercheurs sont en train de déployer des efforts pour raviver l'intérêt pour la langue.[66]

L'allemand comme langue étrangère[[[[modifier]

À l'instar du français et de l'espagnol, l'allemand est devenu une deuxième langue étrangère classique dans le monde occidental, l'anglais (l'espagnol aux États-Unis) étant bien établi comme première langue étrangère.[3][67] L'allemand se classe au deuxième rang (après l'anglais) parmi les langues étrangères les plus connues de l'UE (à égalité avec le français)[3] ainsi qu'en Russie.[68] En termes de nombre d'étudiants à tous les niveaux d'enseignement, l'allemand se classe au troisième rang des pays de l'UE (après l'anglais et le français)[38] ainsi qu'aux Etats-Unis (après l'espagnol et le français).[11][69] En 2015, environ 15,4 millions de personnes apprenaient l'allemand à tous les niveaux d'enseignement dans le monde.[67] Comme ce nombre est resté relativement stable depuis 2005 (± 1 million), environ 75 à 100 millions de personnes capables de communiquer en allemand comme langue étrangère peuvent être déduites en supposant une durée moyenne de cours de trois ans et d’autres paramètres.[2] Selon une enquête réalisée en 2012, 47 millions de personnes au sein de l’UE (soit jusqu’à deux tiers des 75 à 100 millions dans le monde) déclaraient avoir des compétences suffisantes en allemand pour pouvoir converser. Au sein de l’UE, sans compter les pays où il est une langue officielle, l’allemand en tant que langue étrangère est le plus populaire en Europe orientale et septentrionale, à savoir la République tchèque, la Croatie, le Danemark, les Pays-Bas, la Slovaquie, la Hongrie, la Slovénie, la Suède et la Pologne.[3][38] L'allemand était autrefois et reste, dans une certaine mesure, une lingua franca dans ces régions d'Europe.[70]

Allemand standard[[[[modifier]

L'allemand standard ne provient pas d'un dialecte traditionnel d'une région spécifique, mais d'une langue écrite. Cependant, il existe des endroits où les dialectes régionaux traditionnels ont été remplacés par de nouvelles langues vernaculaires basées sur l'allemand standard; c'est le cas dans de vastes régions du nord de l'Allemagne, mais aussi dans les grandes villes d'autres régions du pays. Il est toutefois important de noter que l'allemand standard parlé diffère grandement de la langue écrite formelle, en particulier en ce qui concerne la grammaire et la syntaxe, dans laquelle elle a été influencée par le langage dialectal.

L'allemand standard diffère régionalement entre les pays germanophones en termes de vocabulaire et de syntagmes, voire de grammaire et d'orthographe. Cette variation ne doit pas être confondue avec la variation des dialectes locaux. Even though the regional varieties of standard German are only somewhat influenced by the local dialects, they are very distinct. German is thus considered a pluricentric language.

In most regions, the speakers use a continuum from more dialectal varieties to more standard varieties according to circumstances.

Varieties of Standard German[[[[modifier]

In German linguistics, German dialects are distinguished from varieties of standard German.

le varieties of standard German refer to the different local varieties of the pluricentric standard German. They differ only slightly in lexicon and phonology. In certain regions, they have replaced the traditional German dialects, especially in Northern Germany.

In the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, mixtures of dialect and standard are very seldom used, and the use of Standard German is largely restricted to the written language, though about 11% of the Swiss residents speak High German (aka Standard German) at home, but mainly due to German immigrants.[72] This situation has been called a medial diglossia. Swiss Standard German is used in the Swiss education system, whereas Austrian Standard German is officially used in the Austrian education system.

A mixture of dialect and standard does not normally occur in Northern Germany either. The traditional varieties there are Low German, whereas Standard German is a High German "variety". Because their linguistic distance to it is greater, they do not mesh with Standard German the way that High German dialects (such as Bavarian, Swabian, Hessian) can.

Dialects[[[[modifier]

German is a member of the West Germanic language of the Germanic family of languages, which in turn is part of the Indo-European language family. The German dialects are the traditional local varieties; many of them are hardly understandable to someone who knows only standard German, and they have great differences in lexicon, phonology and syntax. If a narrow definition of language based on mutual intelligibility is used, many German dialects are considered to be separate languages (for instance in the Ethnologue). However, such a point of view is unusual in German linguistics.[2]

The German dialect continuum is traditionally divided most broadly into High German and Low German, also called Low Saxon. However, historically, High German dialects and Low Saxon/Low German dialects do not belong to the same language. Nevertheless, in today's Germany, Low Saxon/Low German is often perceived as a dialectal variation of Standard German on a functional level even by many native speakers. The same phenomenon is found in the eastern Netherlands, as the traditional dialects are not always identified with their Low Saxon/Low German origins, but with Dutch.[73]

The variation among the German dialects is considerable, with often only neighbouring dialects being mutually intelligible. Some dialects are not intelligible to people who know only Standard German. However, all German dialects belong to the dialect continuum of High German and Low Saxon.

Low German/Low Saxon[[[[modifier]

Middle Low German was the lingua franca of the Hanseatic League. It was the predominant language in Northern Germany until the 16th century. In 1534, the Luther Bible was published. The translation is considered to be an important step towards the evolution of the Early New High German. It aimed to be understandable to a broad audience and was based mainly on Central and Upper German varieties. The Early New High German language gained more prestige than Low German and became the language of science and literature. Around the same time, the Hanseatic League, based around northern ports, lost its importance as new trade routes to Asia and the Americas were established, and the most powerful German states of that period were located in Middle and Southern Germany.

The 18th and 19th centuries were marked by mass education in Standard German in schools. Gradually, Low German came to be politically viewed as a mere dialect spoken by the uneducated. Today, Low Saxon can be divided in two groups: Low Saxon varieties with a reasonable Standard German influx[[[[clarification nécessaire] and varieties of Standard German with a Low Saxon influence known as Missingsch. Sometimes, Low Saxon and Low Franconian varieties are grouped together because both are unaffected by the High German consonant shift. However, the proportion of the population who can understand and speak it has decreased continuously since World War II. The largest cities in the Low German area are Hamburg and Dortmund.

Low Franconian[[[[modifier]

The Low Franconian dialects are the dialects that are more closely related to Dutch than to Low German. Most of the Low Franconian dialects are spoken in the Netherlands and in Belgium, where they are considered as dialects of Dutch, which is itself a Low Franconian language. In Germany, Low Franconian dialects are spoken in the northwest of North Rhine-Westphalia, along the Lower Rhine. The Low Franconian dialects spoken in Germany are referred to as Meuse-Rhenish or Low Rhenish. In the north of the German Low Franconian language area, North Low Franconian dialects (also referred to as Cleverlands or as dialects of South Guelderish) are spoken. These dialects are more closely related to Dutch (also North Low Franconian) than the South Low Franconian dialects (also referred to as East Limburgish and, east of the Rhine, Bergish), which are spoken in the south of the German Low Franconian language area. The South Low Franconian dialects are more closely related to Limburgish than to Dutch, and are transitional dialects between Low Franconian and Ripuarian (Central Franconian). The East Bergish dialects are the easternmost Low Franconian dialects, and are transitional dialects between North- and South Low Franconian, and Westphalian (Low German), with most of its features however being North Low Franconian. The largest cities in the German Low Franconian area are Düsseldorf and Duisburg.

High German[[[[modifier]

The High German dialects consist of the Central German, High Franconian, and Upper German dialects. The High Franconian dialects are transitional dialects between Central- and Upper German. The High German varieties spoken by the Ashkenazi Jews have several unique features, and are considered as a separate language, Yiddish, written with the Hebrew alphabet.

Central German[[[[modifier]

The Central German dialects are spoken in Central Germany, from Aachen in the west to Görlitz in the east. They consist of Franconian dialects in the west (West Central German), and non-Franconian dialects in the east (East Central German). Modern Standard German is mostly based on Central German dialects.

The Franconian, West Central German dialects are the Central Franconian dialects (Ripuarian and Moselle Franconian), and the Rhine Franconian dialects (Hessian and Palatine). These dialects are considered as

Luxembourgish as well as the Transylvanian Saxon dialect spoken in Transylvania are based on Moselle Franconian dialects. The largest cities in the Franconian Central German area are Cologne and Frankfurt.

Further east, the non-Franconian, East Central German dialects are spoken (Thuringian, Upper Saxon, Ore Mountainian, and Lusatian-New Markish, and earlier, in the then German-speaking parts of Silesia also Silesian, and in then German southern East Prussia also High Prussian). The largest cities in the East Central German area are Berlin and Leipzig.

High Franconian[[[[modifier]

The High Franconian dialects are transitional dialects between Central- and Upper German. They consist of the East- and South Franconian dialects.

The East Franconian dialect branch is one of the most spoken dialect branches in Germany. These dialects are spoken in the region of Franconia and in the central parts of Saxon Vogtland. Franconia consists of the Bavarian districts of Upper-, Middle-, and Lower Franconia, the region of South Thuringia (Thuringia), and the eastern parts of the region of Heilbronn-Franken (Tauber Franconia and Hohenlohe) in Baden-Württemberg. The largest cities in the East Franconian area are Nuremberg and Würzburg.

South Franconian is mainly spoken in northern Baden-Württemberg in Germany, but also in the northeasternmost part of the region of Alsace in France. While these dialects are considered as dialects of German in Baden-Württemberg, they are considered as dialects of Alsatian in Alsace (most Alsatian dialects are however Low Alemannic). The largest cities in the South Franconian area are Karlsruhe and Heilbronn.

Upper German[[[[modifier]

The Upper German dialects are the Alemannic dialects in the west, and the Bavarian dialects in the east.

Alemannic[[[[modifier]

Alemannic dialects are spoken in Switzerland (High Alemannic in the densely populated Swiss Plateau, in the south also Highest Alemannic, and Low Alemannic in Basel), Baden-Württemberg (Swabian and Low Alemannic, in the southwest also High Alemannic), Bavarian Swabia (Swabian, in the southwesternmost part also Low Alemannic), Vorarlberg (Low-, High-, and Highest Alemannic), Alsace (Low Alemannic, in the southernmost part also High Alemannic), Liechtenstein (High- and Highest Alemannic), and in the Tyrolean district of Reutte (Swabian). The Alemannic dialects are considered as Alsatian in Alsace. The largest cities in the Alemannic area are Stuttgart and Zürich.

Bavarian[[[[modifier]

Bavarian dialects are spoken in Austria (Vienna, Lower- and Upper Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Salzburg, Burgenland, and in most parts of Tyrol), Bavaria (Upper- and Lower Bavaria as well as Upper Palatinate), South Tyrol, southwesternmost Saxony (Southern Vogtlandian), and in the Swiss village of Samnaun. The largest cities in the Bavarian area are Vienna and Munich.

Grammaire[[[[modifier]

German is a fusional language with a moderate degree of inflection, with three grammatical genders; as such, there can be a large number of words derived from the same root.

Noun inflection[[[[modifier]

German nouns inflect by case, gender and number:

- four cases: nominative, accusative, genitive and dative.

- three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. Word endings sometimes reveal grammatical gender: for instance, nouns ending in -ung (-ing), -schaft (-ship), -keit ou heit (-hood, -ness) are feminine, and nouns ending in -chen ou -lein (diminutive forms) are neuter and nouns ending in -ismus (-ism) are masculine. Others are more variable, sometimes depending on the region in which the language is spoken; and some endings are not restricted to one gender, e.g. -er (-er), e.g. Feier (feminine), celebration, party, Arbeiter (masculine), labourer, and Gewitter (neuter), thunderstorm.

- two numbers: singular and plural.

This degree of inflection is considerably less than in Old High German and other old Indo-European languages such as Latin, Ancient Greek and Sanskrit, and it is also somewhat less than, for instance, Old English, modern Icelandic or Russian. The three genders have collapsed in the plural. With four cases and three genders plus plural, there are 16 permutations of case and gender/number of the article (not the nouns), but there are only six forms of the definite article, which together cover all 16 permutations. In nouns, inflection for case is required in the singular for strong masculine and neuter nouns only in the genitive and in the dative (only in fixed or archaic expression), and even this is losing ground to substitutes in informal speech.[74] The dative noun ending is considered archaic or at least old-fashioned in almost all contexts and is almost always dropped even in writing, except in proverbs and other petrified forms. Weak masculine nouns share a common case ending for genitive, dative and accusative in the singular. Feminine nouns are not declined in the singular. The plural has an inflection for the dative. In total, seven inflectional endings (not counting plural markers) exist in German: -s, -es, -n, -ns, -en, -ens, -e.

In German orthography, nouns and most words with the syntactical function of nouns are capitalised to make it easier for readers to determine the function of a word within a sentence (Am Freitag ging ich einkaufen. – "On Friday I went shopping."; Eines Tages kreuzte er endlich auf. – "One day he finally showed up.") This convention is almost unique to German today (shared perhaps only by the closely related Luxembourgish language and several insular dialects of the North Frisian language), but it was historically common in other languages such as Danish (which abolished the capitalization of nouns in 1948) and English.

Like the other Germanic languages, German forms noun compounds in which the first noun modifies the category given by the second,: Hundehütte ("dog hut"; specifically: "dog kennel"). Unlike English, whose newer compounds or combinations of longer nouns are often written in "open" with separating spaces, German (like some other Germanic languages) nearly always uses the "closed" form without spaces, for example: Baumhaus ("tree house"). Like English, German allows arbitrarily long compounds in theory (see also English compounds). The longest German word verified to be actually in (albeit very limited) use is Rindfleischetikettierungsüberwachungsaufgabenübertragungsgesetz, which, literally translated, is "beef labelling supervision duty assignment law"[from[from[from[fromRind (cattle), Fleisch (meat), Etikettierung(s) (labelling), Überwachung(s) (supervision), Aufgaben (duties), Übertragung(s) (assignment), Gesetz (law)]. However, examples like this are perceived by native speakers as excessively bureaucratic, stylistically awkward or even satirical.

Verb inflection[[[[modifier]

The inflection of standard German verbs includes:

- two main conjugation classes: weak and strong (as in English). Additionally, there is a third class, known as mixed verbs, whose conjugation combines features of both the strong and weak patterns.

- three persons: first, second and third.

- two numbers: singular and plural.

- three moods: indicative, imperative and subjunctive (in addition to infinitive)

- two voices: active and passive. The passive voice uses auxiliary verbs and is divisible into static and dynamic. Static forms show a constant state and use the verb ’’to be’’ (sein). Dynamic forms show an action and use the verb “to become’’ (werden).

- two tenses without auxiliary verbs (present and preterite) and four tenses constructed with auxiliary verbs (perfect, pluperfect, future and future perfect).

- the distinction between grammatical aspects is rendered by combined use of subjunctive and/or preterite marking so the plain indicative voice uses neither of those two markers; the subjunctive by itself conveys secondhand information[[[[clarification nécessaire]; subjunctive plus preterite marks the conditional state; and the preterite alone shows either plain indicative (in the past), or functions as a (literal) alternative for either second-hand-information or the conditional state of the verb, when necessary for clarity.

- the distinction between perfect and progressive aspect is and has, at every stage of development, been a productive category of the older language and in nearly all documented dialects, but, strangely enough, it is now rigorously excluded from written usage in its present normalised form.

- disambiguation of completed vs. uncompleted forms is widely observed and regularly generated by common prefixes (blicken [to look], erblicken [tosee –unrelatedform:[tosee –unrelatedform:[tosee –unrelatedform:[tosee –unrelatedform:sehen]).

Verb prefixes[[[[modifier]

The meaning of basic verbs can be expanded and sometimes radically changed through the use of a number of prefixes. Some prefixes have a specific meaning; le préfixe zer- refers to destruction, as in zerreißen (to tear apart), zerbrechen (to break apart), zerschneiden (to cut apart). Other prefixes have only the vaguest meaning in themselves; ver- is found in a number of verbs with a large variety of meanings, as in versuchen (to try) from suchen (to seek), vernehmen (to interrogate) from nehmen (to take), verteilen (to distribute) from teilen (to share), verstehen (to understand) from stehen (to stand).

Other examples include the following:

haften (to stick), verhaften (to detain); kaufen (to buy), verkaufen (to sell); hören (to hear), aufhören (to cease); fahren (to drive), heufahren (to experience).

Many German verbs have a separable prefix, often with an adverbial function. In finite verb forms, it is split off and moved to the end of the clause and is hence considered by some to be a "resultative particle". Par exemple, mitgehen, meaning "to go along", would be split, giving Gehen Sie mit? (Literal: "Go you with?"; Idiomatic: "Are you going along?").

Indeed, several parenthetical clauses may occur between the prefix of a finite verb and its complement (ankommen = to arrive, er kam an = he arrived, er ist angekommen = he has arrived):

- Er kam am Freitagabend nach einem harten Arbeitstag und dem üblichen Ärger, der ihn schon seit Jahren immer wieder an seinem Arbeitsplatz plagt, mit fraglicher Freude auf ein Mahl, das seine Frau ihm, wie er hoffte, bereits aufgetischt hatte, endlich zu Hause un.

A selectively literal translation of this example to illustrate the point might look like this:

- He "came" on Friday evening, after a hard day at work and the usual annoyances that had time and again been troubling him for years now at his workplace, with questionable joy, to a meal which, as he hoped, his wife had already put on the table, finally at home "on".

Word order[[[[modifier]

German word order is generally with the V2 word order restriction and also with the SOV word order restriction for main clauses. For polar questions, exclamations and wishes, the finite verb always has the first position. In subordinate clauses, the verb occurs at the very end.

German requires for a verbal element (main verb or auxiliary verb) to appear second in the sentence. The verb is preceded by the topic of the sentence. The element in focus appears at the end of the sentence. For a sentence without an auxiliary, these are some possibilities:

- Der alte Mann gab mir gestern das Buch. (The old man gave me yesterday the book; normal order)

- Das Buch gab mir gestern der alte Mann. (The book gave [to] me yesterday the old man)

- Das Buch gab der alte Mann mir gestern. (The book gave the old man [to] me yesterday)

- Das Buch gab mir der alte Mann gestern. (The book gave [to] me the old man yesterday)

- Gestern gab mir der alte Mann das Buch. (Yesterday gave [to] me the old man the book, normal order)

- Mir gab der alte Mann das Buch gestern. ([To] me gave the old man the book yesterday (entailing: as for you, it was another date))

The position of a noun in a German sentence has no bearing on its being a subject, an object or another argument. In a declarative sentence in English, if the subject does not occur before the predicate, the sentence could well be misunderstood.

However, German's flexibile word order allows one to emphasise specific words:

Normal word order:

-

- Der Direktor betrat gestern um 10 Uhr mit einem Schirm in der Hand sein Büro.

- The manager entered yesterday at 10 o'clock with an umbrella in the hand his office.

Object in front:

-

- Sein Büro betrat der Direktor gestern um 10 Uhr mit einem Schirm in der Hand.

- His office entered the manager yesterday at 10 o'clock with an umbrella in the hand.

- The object Sein Büro (his office) is thus highlighted; it could be the topic of the next sentence.

Adverb of time in front:

-

- Gestern betrat der Direktor um 10 Uhr mit einem Schirm in der Hand sein Büro. (aber heute ohne Schirm)

- Yesterday entered the manager at 10 o'clock with an umbrella in the hand his office. (but today without umbrella)

Both time expressions in front:

-

- Gestern um 10 Uhr betrat der Direktor mit einem Schirm in der Hand sein Büro.

- Yesterday at 10 o'clock entered the manager with an umbrella in the hand his office.

- The full-time specification Gestern um 10 Uhr is highlighted.

Another possibility:

-

- Gestern um 10 Uhr betrat der Direktor sein Büro mit einem Schirm in der Hand.

- Yesterday at 10 o'clock the manager entered his office with an umbrella in his hand.

- Both the time specification and the fact he carried an umbrella are accentuated.

Swapped adverbs:

-

- Der Direktor betrat mit einem Schirm in der Hand gestern um 10 Uhr sein Büro.

- The manager entered with an umbrella in the hand yesterday at 10 o'clock his office.

- La phrase mit einem Schirm in der Hand is highlighted.

Swapped object:

-

- Der Direktor betrat gestern um 10 Uhr sein Büro mit einem Schirm in der Hand.

- The manager entered yesterday at 10 o'clock his office with an umbrella in his hand.

- The time specification and the object sein Büro (his office) are lightly accentuated.

The flexible word order also allows one to use language "tools" (such as poetic meter and figures of speech) more freely.

Auxiliary verbs[[[[modifier]

When an auxiliary verb is present, it appears in second position, and the main verb appears at the end. This occurs notably in the creation of the perfect tense. Many word orders are still possible:

- Der alte Mann hat mir heute das Buch gegeben. (The old man has me today the book given.)

- Das Buch hat der alte Mann mir heute gegeben. (The book has the old man me today given.)

- Heute hat der alte Mann mir das Buch gegeben. (Aujourd'hui has the old man me the book given.)

The main verb may appear in first position to put stress on the action itself. The auxiliary verb is still in second position.

- Gegeben hat mir der alte Mann das Buch heute. (Given has me the old man the book 'today'.) The bare fact that the book has been given is emphasized, as well as 'today'.

Modal verbs[[[[modifier]

Sentences using modal verbs place the infinitive at the end. For example, the English sentence "Should he go home?" would be rearranged in German to say "Should he (to) home go?" (Soll er nach Hause gehen?). Thus, in sentences with several subordinate or relative clauses, the infinitives are clustered at the end. Compare the similar clustering of prepositions in the following (highly contrived) English sentence: "What did you bring that book that I do not like to be read to out of up for?"

Multiple infinitives[[[[modifier]

German subordinate clauses have all verbs clustered at the end. Given that auxiliaries encode future, passive, modality, and the perfect, very long chains of verbs at the end of the sentence can occur. In these constructions, the past participle in ge- is often replaced by the infinitive.

- Man nimmt an, dass der Deserteur wohl erschossenV wordenpsv seinperf sollmod

- One suspects that the deserter probably shot become be should.

- ("It is suspected that the deserter probably had been shot")

-

- Er wusste nicht, dass der Agent einen Nachschlüssel hatte machen lassen

- He knew not that the agent a picklock had make let

-

- Er wusste nicht, dass der Agent einen Nachschlüssel machen lassen hatte

- He knew not that the agent a picklock make let had

- ("He did not know that the agent had had a picklock made")

The order at the end of such strings is subject to variation, but the latter version is unusual.

Vocabulary[[[[modifier]

Most German vocabulary is derived from the Germanic branch of the European language family.[[[[citation requise] However, there is a significant amount of loanwords from other languages, in particular from Latin, Greek, Italian, French[75] and most recently English.[76] In the early 19th century, Joachim Heinrich Campe estimated that one fifth of the total German vocabulary was of French or Latin origin.[77]

Latin words were already imported into the predecessor of the German language during the Roman Empire and underwent all the characteristic phonetic changes in German. Their origin is thus no longer recognizable for most speakers (e.g. Pforte, Tafel, Mauer, Käse, Köln from Latin porta, tabula, murus, caseus, Colonia). Borrowing from Latin continued after the fall of the Roman Empire during Christianization, mediated by the church and monasteries. Another important influx of Latin words can be observed during Renaissance humanism. In a scholarly context, the borrowings from Latin have continued until today, in the last few decades often indirectly through borrowings from English. During the 15th to 17th centuries, the influence of Italian was great, leading to many Italian loanwords in the fields of architecture, finance, and music. The influence of the French language in the 17th to 19th centuries resulted in an even greater import of French words. The English influence was already present in the 19th century, but it did not become dominant until the second half of the 20th century.

At the same time, the effectiveness of the German language in forming equivalents for foreign words from its inherited Germanic stem repertory is great.[[[[citation requise] Thus, Notker Labeo was able to translate Aristotelian treatises in pure (Old High) German in the decades after the year 1000. The tradition of loan translation was revitalized in the 18th century, with linguists like Joachim Heinrich Campe, who introduced close to 300 words that are still used in modern German. Even today, there are movements that try to promote the Ersatz (substitution) of foreign words deemed unnecessary with German alternatives.[78] It is claimed that this would also help in spreading modern or scientific notions among the less educated and as well democratise public life.

As in English, there are many pairs of synonyms due to the enrichment of the Germanic vocabulary with loanwords from Latin and Latinized Greek. These words often have different connotations from their Germanic counterparts and are usually perceived as more scholarly.

- Historie, historisch – "history, historical", (Geschichte, geschichtlich)

- Humanität, human – "humaneness, humane", (Menschlichkeit, menschlich)[79]

- Millennium – "millennium", (Jahrtausend)

- Perzeption – "perception", (Wahrnehmung)

- Vokabular – "vocabulary", (Wortschatz)

The size of the vocabulary of German is difficult to estimate. le Deutsches Wörterbuch (The German Dictionary) initiated by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm already contained over 330,000 headwords in its first edition. The modern German scientific vocabulary is estimated at nine million words and word groups (based on the analysis of 35 million sentences of a corpus in Leipzig, which as of July 2003 included 500 million words in total).[80]

The Duden is the de facto official dictionary of the German language, first published by Konrad Duden in 1880. The Duden is updated regularly, with new editions appearing every four or five years. As of August 2017[update], it is in its 27th edition and in 12 volumes, each covering different aspects such as loanwords, etymology, pronunciation, synonyms, and so forth.

The first of these volumes, Die deutsche Rechtschreibung (German Orthography), has long been the prescriptive source for the spelling of German. le Duden has become the bible of the German language, being the definitive set of rules regarding grammar, spelling and usage of German.[81]

le Österreichisches Wörterbuch ("Austrian Dictionary"), abbreviated ÖWB, is the official dictionary of the German language in the Republic of Austria. It is edited by a group of linguists under the authority of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture (German:Bundesministerium für Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur). It is the Austrian counterpart to the German Duden and contains a number of terms unique to Austrian German or more frequently used or differently pronounced there.[82] A considerable amount of this "Austrian" vocabulary is also common in Southern Germany, especially Bavaria, and some of it is used in Switzerland as well. The most recent edition is the 42nd from 2012. Since the 39th edition from 2001 the orthography of the ÖWB was adjusted to the German spelling reform of 1996. The dictionary is also officially used in the Italian province of South Tyrol.

English–German cognates[[[[modifier]

This is a selection of cognates in both English and German. Instead of the usual infinitive ending -en German verbs are indicated by a hyphen "-" after their stems. Words that are written with capital letters in German are nouns.

| Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| et | und | bras | Bras | ours | Bär | castor | Biber | abeille | Biene | Bière | Bier | meilleur | meilleur | meilleur | besser | cligner | blink- | Floraison | blüh- | |||||||||

| bleu | blau | bateau | Démarrage | livre | Buch | brasser | brau- | brewery | Brauerei | pont | Brücke | front | Braue | marron | braun | gazouiller | zirp- | église | Kirche | |||||||||

| du froid | kalt | cool | kühl | vallée | Tal | barrage | Damm | Danse | tanz- | pâte | Teig | rêver | Traum | rêver | träum- | boisson | Getränk | boisson | trink- | |||||||||

| oreille | Ohr | Terre | Erde | manger | ess- | loin | fougère | plume | Feder | fougère | Farn | champ | Feld | doigt | Finger | poisson | Fisch | pêcheur | Fischer | |||||||||

| fuir | flieh- | vol | Flug | inonder | Flut | couler | fließ- | couler | Fluss | voler | Fliege | voler | flieg- | pour | für | gué | Furt | quatre | vier | |||||||||

| Renard | Fuchs | fruit | Frucht | verre | Glas | aller | geh- | or | Or | bien | intestin | herbe | Gras | sauterelle | Grashüpfer | vert | grün | gris | grau | |||||||||

| vieille sorcière | Hexe | saluer | Hagel | main | Main | chapeau | cabane | haine | Hass | havre | Hafen | foins | Heu | entendre | hör- | cœur | Herz | chaleur | Hitze | |||||||||

| bruyère | Heide | haute | hoch | mon chéri | Honig | frelon | Hornisse | cent | hundert | faim | Faim | cabane | Hütte | la glace | Eis | Roi | König | baiser | Kuss | |||||||||

| baiser | küss- | le genou | Knie | terre | Terre | atterrissage | Landung | rire | lach- | lie, lay | lieg-, lag | lie, lied | lüg-, log | lumière (UNE) | leicht | lumière | Licht | vivre | leb- | |||||||||

| foie | Leber | amour | Liebe | homme | Mann | milieu | Mitte | minuit | Mitternacht | lune | Mond | mousse | Moos | bouche | Mund | bouche (river) | Mündung | nuit | Nacht | |||||||||

| nez | Nase | écrou | Nuss | plus de | über | plante | Pflanze | charlatan | quak- | pluie | Regen | arc en ciel | Regenbogen | rouge | pourrir | bague | Bague | le sable | Le sable | |||||||||

| dire | sag- | mer | Voir (F) | couture | Saum | siège | Sitz | voir | seh- | mouton | Schaf | miroiter | schimmer- | éclat | schein- | navire | Schiff | argent | Silber | |||||||||

| chanter | sing- | asseoir | sitz- | neige | Schnee | âme | Seele | parler | sprech- | printemps | spring- | étoile | Stern | point | Stich | cigogne | Storch | orage | Sturm | |||||||||

| orageux | stürmisch | brin | strand- | paille | Stroh | balle de paille | Strohballen | courant | Strom | courant | ström- | bégaiement | stotter- | été | Sommer | Soleil | Sonne | ensoleillé | sonnig | |||||||||

| cygne | Schwan | dire | erzähl- | cette (C) | dass | la | der, die, das, den, dem | puis | dann | la soif | Durst | chardon | Distel | épine | Dorn | mille | tausend | tonnerre | Donner | |||||||||

| gazouillement | zwitscher- | plus haut | ober | chaud | chaud | guêpe | Wespe | eau | Wasser | Météo | Wetter | tisser | web- | bien | Quelle | bien | wohl | lequel | welch | |||||||||

| blanc | weiß | sauvage | sauvage | vent | Vent | hiver | Hiver | Loup | Loup | mot | Moût | monde | Welt | fil | Garn | année | Jahr | jaune | gelb | |||||||||

| Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand | Anglais | allemand |

Orthography[[[[modifier]

German is written in the Latin alphabet. In addition to the 26 standard letters, German has three vowels with Umlaut, namely une, ö et ü, as well as the eszett or scharfes s (sharp s): ß. In Switzerland and Liechtenstein, ss is used instead of ß. Puisque ß can never occur at the beginning of a word, it has no traditional uppercase form.

Written texts in German are easily recognisable as such by distinguishing features such as umlauts and certain orthographical features – German is the only major language that capitalizes all nouns, a relic of a widespread practice in Northern Europe in the early modern era (including English for a while, in the 1700s) – and the frequent occurrence of long compounds. The longest German word that has been published is Donaudampfschiffahrtselektrizitätenhauptbetriebswerkbauunterbeamtengesellschaft made of 79 characters. Because legibility and convenience set certain boundaries, compounds consisting of more than three or four nouns are almost exclusively found in humorous contexts. (In contrast, although English can also string nouns together, it usually separates the nouns with spaces. For example, "toilet bowl cleaner".)

Present[[[[modifier]

Before the German orthography reform of 1996, ß remplacé ss after long vowels and diphthongs and before consonants, word-, or partial-word-endings. In reformed spelling, ß remplace ss only after long vowels and diphthongs.

Since there is no traditional capital form of ß, it was replaced by SS when capitalization was required. Par exemple, Maßband (tape measure) became MASSBAND in capitals. An exception was the use of ß in legal documents and forms when capitalizing names. To avoid confusion with similar names, lower case ß was maintained (so, "KREßLEIN" instead of "KRESSLEIN"). Capital ß (ẞ) was ultimately adopted into German orthography in 2017, ending a long orthographic debate.[83]

Umlaut vowels (ä, ö, ü) are commonly transcribed with ae, oe, and ue if the umlauts are not available on the keyboard or other medium used. In the same manner ß can be transcribed as ss. Some operating systems use key sequences to extend the set of possible characters to include, amongst other things, umlauts; in Microsoft Windows this is done using Alt codes. German readers understand these transcriptions (although they appear unusual), but they are avoided if the regular umlauts are available because they are a makeshift, not proper spelling. (In Westphalia and Schleswig-Holstein, city and family names exist where the extra e has a vowel lengthening effect, e.g. Raesfeld [ˈraːsfɛlt], Coesfeld [ˈkoːsfɛlt] et Itzehoe [ɪtsəˈhoː], but this use of the letter e after a/o/u does not occur in the present-day spelling of words other than proper nouns.)

There is no general agreement on where letters with umlauts occur in the sorting sequence. Telephone directories treat them by replacing them with the base vowel followed by an e. Some dictionaries sort each umlauted vowel as a separate letter after the base vowel, but more commonly words with umlauts are ordered immediately after the same word without umlauts. As an example in a telephone book Ärzte occurs after Adressenverlage mais avant Anlagenbauer (because Ä is replaced by Ae). In a dictionary Ärzte vient après Arzt, but in some dictionaries Ärzte and all other words starting with UNE may occur after all words starting with UNE. In some older dictionaries or indexes, initial Sch et St are treated as separate letters and are listed as separate entries after S, but they are usually treated as S+C+H and S+T.

Written German also typically uses an alternative opening inverted comma (quotation mark) as in „Guten Morgen!“.

Past[[[[modifier]

Until the early 20th century, German was mostly printed in blackletter typefaces (mostly in Fraktur, but also in Schwabacher) and written in corresponding handwriting (for example Kurrent and Sütterlin). These variants of the Latin alphabet are very different from the serif or sans-serif Antiqua typefaces used today, and the handwritten forms in particular are difficult for the untrained to read. The printed forms, however, were claimed by some to be more readable when used for Germanic languages.[84] (Often, foreign names in a text were printed in an Antiqua typeface even though the rest of the text was in Fraktur.) The Nazis initially promoted Fraktur and Schwabacher because they were considered Aryan, but they abolished them in 1941, claiming that these letters were Jewish.[85] It is also believed that the Nazi régime had banned this script as they realized that Fraktur would inhibit communication in the territories occupied during World War II.[86]

The Fraktur script however remains present in everyday life in pub signs, beer brands and other forms of advertisement, where it is used to convey a certain rusticality and antiquity.

A proper use of the long s, (langes s), ſ, is essential for writing German text in Fraktur typefaces. Many Antiqua typefaces include the long s also. A specific set of rules applies for the use of long s in German text, but nowadays it is rarely used in Antiqua typesetting. Any lower case "s" at the beginning of a syllable would be a long s, as opposed to a terminal s or short s (the more common variation of the letter s), which marks the end of a syllable; for example, in differentiating between the words Wachſtube (guard-house) and Wachstube (tube of polish/wax). One can easily decide which "s" to use by appropriate hyphenation, (Wach-ſtube contre. Wachs-tube). The long s only appears in lower case.

Reform of 1996[[[[modifier]

The orthography reform of 1996 led to public controversy and considerable dispute. The states (Bundesländer) of North Rhine-Westphalia and Bavaria would not accept it. The dispute landed at one point in the highest court, which made a short issue of it, claiming that the states had to decide for themselves and that only in schools could the reform be made the official rule – everybody else could continue writing as they had learned it. After 10 years, without any intervention by the federal parliament, a major revision was installed in 2006, just in time for the coming school year. In 2007, some traditional spellings were finally invalidated, whereas in 2008, on the other hand, many of the old comma rules were again put in force.

The most noticeable change was probably in the use of the letter ß, called scharfes s (Sharp S) ou ess-zett (pronounced ess-tsett). Traditionally, this letter was used in three situations:

- After a long vowel or vowel combination,

- Before a t, et

- At the end of a syllable

Ainsi Füße, paßt, et daß. Currently only the first rule is in effect, thus Füße, passt, et dass. Le mot Fuß 'foot' has the letter ß because it contains a long vowel, even though that letter occurs at the end of a syllable. The logic of this change is that an 'ß' is a single letter whereas 'ss' obviously are two letters, so the same distinction applies as for instance between the words den et denn.

Phonology[[[[modifier]

Vowels[[[[modifier]

In German, vowels (excluding diphthongs; see below) are either court ou longue, as follows:

| UNE | UNE | E | je | O | Ö | U | Ü | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| court | /a/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/, /ə/ | /ɪ/ | /ɔ/ | /œ/ | /ʊ/ | /ʏ/ |

| longue | /aː/ | /ɛː/, /eː/ | /eː/ | /iː/ | /oː/ | /øː/ | /uː/ | /yː/ |

Short /ɛ/ is realized as [ɛ] in stressed syllables (including secondary stress), but as [ə] in unstressed syllables. Note that stressed short /ɛ/ can be spelled either with e ou avec une (for instance, hätte "would have" and Kette "chain" rhyme). In general, the short vowels are open and the long vowels are close. The one exception is the open /ɛː/ sound of long UNE; in some varieties of standard German, /ɛː/ et /eː/ have merged into [eː], removing this anomaly. In that case, pairs like Bären/Beeren 'bears/berries' or Ähre/Ehre 'spike (of wheat)/honour' become homophonous (see: Captain Bluebear).

In many varieties of standard German, an unstressed /ɛr/ n'est pas prononcé [ər], but vocalised to [ɐ].

Whether any particular vowel letter represents the long or short phoneme is not completely predictable, although the following regularities exist:

- If a vowel (other than je) is at the end of a syllable or followed by a single consonant, it is usually pronounced long (e.g. Hof [hoːf]).

- If a vowel is followed by h or if an je is followed by an e, it is long.

- If the vowel is followed by a double consonant (e.g. ff, ss ou tt), ck, tz or a consonant cluster (e.g. st ou Dakota du Nord), it is nearly always short (e.g. hoffen [ˈhɔfən]). Double consonants are used only for this function of marking preceding vowels as short; the consonant itself is never pronounced lengthened or doubled, in other words this is not a feeding order of gemination and then vowel shortening.